Ten Commandments

| Part of a series on |

| The Ten Commandments |

|---|

|

|

Related articles |

|

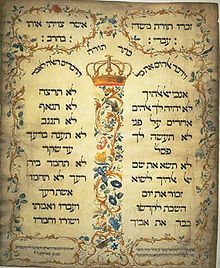

This 1768 parchment (612×502 mm) by Jekuthiel Sofer emulated the 1675 Ten Commandments at the Amsterdam Esnoga synagogue.[1]

The Ten Commandments (Hebrew: עֲשֶׂרֶת הַדִּבְּרוֹת, Aseret ha'Dibrot), also known as the Decalogue, are a set of biblical principles relating to ethics and worship, which play a fundamental role in Judaism and Christianity. The commandments include instructions to worship only God, to honour one's parents, and to keep the sabbath, as well as prohibitions against idolatry, blasphemy, murder, adultery, theft, dishonesty, and coveting. Different religious groups follow different traditions for interpreting and numbering them.

The Ten Commandments appear twice in the Hebrew Bible, in the books of Exodus and Deuteronomy. Modern scholarship has found likely influences in Hittite and Mesopotamian laws and treaties, but is divided over exactly when the Ten Commandments were written and who wrote them.

Contents

1 Terminology

2 The Ten Commandments

3 Religious interpretations

3.1 Judaism

3.1.1 Two tablets

3.1.2 Use in Jewish ritual

3.2 Samaritan

3.3 Christianity

3.3.1 References in the New Testament

3.3.2 Roman Catholicism

3.3.3 Orthodox

3.3.4 Protestantism

3.3.4.1 Lutheranism

3.3.4.2 Reformed

3.3.4.3 Methodist

3.3.5 The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

3.4 Main points of interpretative difference

3.4.1 Sabbath day

3.4.2 Killing or murder

3.4.3 Theft

3.4.4 Idolatry

3.4.5 Adultery

4 Critical historical analysis

4.1 Early theories

4.2 Hittite treaties

4.3 Dating

4.4 The Ritual Decalogue

5 United States debate over display on public property

6 Cultural references

7 See also

8 References

9 Further reading

10 External links

Terminology

Part of the All Souls Deuteronomy, containing one of the oldest extant copies of the Decalogue

In biblical Hebrew, the Ten Commandments are called עשרת הדברים (transliterated aseret ha-d'varîm) and in Rabbinical Hebrew עשרת הדברות (transliterated aseret ha-dibrot), both translatable as "the ten words", "the ten sayings", or "the ten matters".[2] The Tyndale and Coverdale English translations used "ten verses". The Geneva Bible used "tenne commandements", which was followed by the Bishops' Bible and the Authorized Version (the "King James" version) as "ten commandments". Most major English versions use "commandments."[3]

The English name "Decalogue" is derived from Greek δεκάλογος, dekalogos, the latter meaning and referring[4] to the Greek translation (in accusative) δέκα λόγους, deka logous, "ten words", found in the Septuagint (or LXX) at Exodus 34:28[3] and Deuteronomy 10:4.[5]

The stone tablets, as opposed to the commandments inscribed on them, are called לוחות הברית, Lukhot HaBrit, meaning "the tablets of the covenant".

The Ten Commandments

Different religious traditions divide the seventeen verses of Exodus 20:1–17 and their parallels at Deuteronomy 5:4–21 into ten "commandments" or "sayings" in different ways, shown in the table below. Some suggest that the number ten is a choice to aid memorization rather than a matter of theology.[6][7]

LXX | P | S | T | A | C | L | R | Main article | Exodus 20:1-17 | Deuteronomy 5:4-21 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| — | — | — | 1 | — | 1 | — | (1) | I am the Lord thy God, which have brought thee out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of bondage. | 2[8] | 6[8] |

| 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 1 | Thou shalt have no other gods before me | 3[9] | 7[9] |

| 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 2 | Thou shalt not make unto thee any graven image | 4–6[10] | 8–10[10] |

| 3 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 3 | Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord thy God in vain | 7[11] | 11[11] |

| 4 | 4 | 3 | 4 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 4 | Remember the sabbath day, to keep it holy | 8–11[12] | 12–15[13] |

| 5 | 5 | 4 | 5 | 4 | 4 | 4 | 5 | Honour thy father and thy mother | 12[14] | 16[15] |

| 6 | 7 | 5 | 6 | 5 | 5 | 5 | 6 | Thou shalt not kill | 13[16] | 17[16] |

| 7 | 6 | 6 | 7 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 7 | Thou shalt not commit adultery | 14[17] | 18[18] |

| 8 | 8 | 7 | 8 | 7 | 7 | 7 | 8 | Thou shalt not steal | 15[19] | 19[20] |

| 9 | 9 | 8 | 9 | 8 | 8 | 8 | 9 | Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbour | 16[21] | 20[22] |

| 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 | Thou shalt not covet (neighbour's house) | 17a[23] | 21b[24] |

| 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 9 | 9 | 10 | 10 | Thou shalt not covet (neighbour's wife) | 17b[25] | 21a[26] |

| 10 | 10 | 9 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | 10 | Thou shalt not covet (neighbour's slaves, animals, or anything else) | 17c[27] | 21c[28] |

| — | — | 10 | — | — | — | — | — | Ye shall erect these stones which I command thee upon Mount Gerizim | [citation needed] | [citation needed] |

- All scripture quotes above are from the King James Version. Click on verses at top of columns for other versions.

Traditions:

LXX: Septuagint, generally followed by Orthodox Christians.

P: Philo, same as the Septuagint, but with the prohibitions on killing and adultery reversed.

S: Samaritan Pentateuch, with an additional commandment about Mount Gerizim as 10th.

T: Jewish Talmud, makes the "prologue" the first "saying" or "matter" and combines the prohibition on worshiping deities other than Yahweh with the prohibition on idolatry.

A: Augustine follows the Talmud in combining verses 3–6, but omits the prologue as a commandment and divides the prohibition on coveting in two and following the word order of Deuteronomy 5:21 rather than Exodus 20:17.

C: Catechism of the Catholic Church, largely follows Augustine.

L: Lutherans follow Luther's Large Catechism, which follows Augustine but omits the prohibition of images[29] and uses the word order of Exodus 20:17 rather than Deuteronomy 5:21 for the ninth and tenth commandments.

R: Reformed Christians follow John Calvin's Institutes of the Christian Religion, which follows the Septuagint; this system is also used in the Anglican Book of Common Prayer.[30]

The biblical narrative of the revelation at Sinai begins in Exodus 19 after the arrival of the children of Israel at Mount Sinai (also called Horeb). On the morning of the third day of their encampment, "there were thunders and lightnings, and a thick cloud upon the mount, and the voice of the trumpet exceeding loud", and the people assembled at the base of the mount. After "the LORD[31] came down upon mount Sinai", Moses went up briefly and returned and prepared the people, and then in Exodus 20 "God spoke" to all the people the words of the covenant, that is, the "ten commandments"[32] as it is written. Modern biblical scholarship differs as to whether Exodus 19-20 describes the people of Israel as having directly heard all or some of the decalogue, or whether the laws are only passed to them through Moses.[33]

The people were afraid to hear more and moved "afar off", and Moses responded with "Fear not." Nevertheless, he drew near the "thick darkness" where "the presence of the Lord" was[34] to hear the additional statutes and "judgments",[35] all which he "wrote"[36] in the "book of the covenant"[37] which he read to the people the next morning, and they agreed to be obedient and do all that the LORD had said. Moses escorted a select group consisting of Aaron, Nadab and Abihu, and "seventy of the elders of Israel" to a location on the mount where they worshipped "afar off"[38] and they "saw the God of Israel" above a "paved work" like clear sapphire stone.[39]

.mw-parser-output .templatequoteoverflow:hidden;margin:1em 0;padding:0 40px.mw-parser-output .templatequote .templatequoteciteline-height:1.5em;text-align:left;padding-left:1.6em;margin-top:0

And the LORD said unto Moses, Come up to me into the mount, and be there: and I will give thee tablets of stone, and a law, and commandments which I have written; that thou mayest teach them. 13 And Moses rose up, and his minister Joshua: and Moses went up into the mount of God.

— First mention of the tablets in Exodus 24:12–13

Moses Breaking the Tablets of the Law (1659) by Rembrandt. (Gemäldegalerie, Berlin)

The mount was covered by the cloud for six days, and on the seventh day Moses went into the midst of the cloud and was "in the mount forty days and forty nights."[40] And Moses said, "the LORD delivered unto me two tablets of stone written with the finger of God; and on them was written according to all the words, which the LORD spake with you in the mount out of the midst of the fire in the day of the assembly."[41] Before the full forty days expired, the children of Israel collectively decided that something had happened to Moses, and compelled Aaron to fashion a golden calf, and he "built an altar before it"[42] and the people "worshipped" the calf.[43]

After the full forty days, Moses and Joshua came down from the mountain with the tablets of stone: "And it came to pass, as soon as he came nigh unto the camp, that he saw the calf, and the dancing: and Moses' anger waxed hot, and he cast the tablets out of his hands, and brake them beneath the mount."[44] After the events in chapters 32 and 33, the LORD told Moses, "Hew thee two tablets of stone like unto the first: and I will write upon these tablets the words that were in the first tablets, which thou brakest."[45] "And he wrote on the tablets, according to the first writing, the ten commandments, which the LORD spake unto you in the mount out of the midst of the fire in the day of the assembly: and the LORD gave them unto me."[46]

According to Jewish tradition, Exodus 20:1–17 constitutes God's first recitation and inscription of the ten commandments on the two tablets,[47] which Moses broke in anger with his rebellious nation, and were later rewritten on replacement stones and placed in the ark of the covenant;[48] and Deuteronomy 5:4–25 consists of God's re-telling of the Ten Commandments to the younger generation who were to enter the Promised Land. The passages in Exodus 20 and Deuteronomy 5 contain more than ten imperative statements, totalling 14 or 15 in all.

Religious interpretations

The Ten Commandments concern matters of fundamental importance in Judaism and Christianity: the greatest obligation (to worship only God), the greatest injury to a person (murder), the greatest injury to family bonds (adultery), the greatest injury to commerce and law (bearing false witness), the greatest inter-generational obligation (honour to parents), the greatest obligation to community (truthfulness), the greatest injury to moveable property (theft).[49]

The Ten Commandments are written with room for varying interpretation, reflecting their role as a summary of fundamental principles.[7][49][50][51] They are not as explicit[49] or detailed as rules[52] or many other biblical laws and commandments, because they provide guiding principles that apply universally, across changing circumstances. They do not specify punishments for their violation. Their precise import must be worked out in each separate situation.[52]

The Bible indicates the special status of the Ten Commandments among all other Torah laws in several ways:

- They have a uniquely terse style.[53]

- Of all the biblical laws and commandments, the Ten Commandments alone[53] are said to have been "written with the finger of God" (Exodus 31:18).

- The stone tablets were placed in the Ark of the Covenant (Exodus 25:21, Deuteronomy 10:2,5).[53]

Judaism

The Ten Commandments form the basis of Jewish law,[54] stating God's universal and timeless standard of right and wrong – unlike the rest of the 613 commandments in the Torah, which include, for example, various duties and ceremonies such as the kashrut dietary laws, and now unobservable rituals to be performed by priests in the Holy Temple.[55] Jewish tradition considers the Ten Commandments the theological basis for the rest of the commandments; a number of works, starting with Rabbi Saadia Gaon, have made groupings of the commandments according to their links with the Ten Commandments.[citation needed]

A conservative rabbi, Louis Ginzberg, stated in his book Legends of the Jews, that Ten Commandments are virtually entwined, that the breaking of one leads to the breaking of another. Echoing an earlier rabbinic comment found in the commentary of Rashi to the Songs of Songs (4:5) Ginzberg explained - there is also a great bond of union between the first five commandments and the last five. The first commandment: "I am the Lord, thy God," corresponds to the sixth: "Thou shalt not kill," for the murderer slays the image of God. The second: "Thou shalt have no strange gods before me," corresponds to the seventh: "Thou shalt not commit adultery," for conjugal faithlessness is as grave a sin as idolatry, which is faithlessness to God. The third commandment: "Thou shalt not take the name of the Lord in vain," corresponds to the eighth: "Thou shalt not steal," for stealing result in false oath in God's name. The fourth: "Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy," corresponds to the ninth: "Thou shalt not bear false witness against thy neighbor," for he who bears false witness against his neighbor commits as grave a sin as if he had borne false witness against God, saying that He had not created the world in six days and rested on the seventh day (the holy Sabbath). The fifth commandment: "Honor thy father and thy mother," corresponds to the tenth: "Covet not thy neighbor's wife," for one who indulges this lust produces children who will not honor their true father, but will consider a stranger their father.[56]

The traditional Rabbinical Jewish belief is that the observance of these commandments and the other mitzvot are required solely of the Jewish people and that the laws incumbent on humanity in general are outlined in the seven Noahide laws, several of which overlap with the Ten Commandments. In the era of the Sanhedrin transgressing any one of six of the Ten Commandments theoretically carried the death penalty, the exceptions being the First Commandment, honouring your father and mother, saying God's name in vain, and coveting, though this was rarely enforced due to a large number of stringent evidentiary requirements imposed by the oral law.[57]

Two tablets

The arrangement of the commandments on the two tablets is interpreted in different ways in the classical Jewish tradition. Rabbi Hanina ben Gamaliel says that each tablet contained five commandments, "but the Sages say ten on one tablet and ten on the other", that is, that the tablets were duplicates.[58] This can be compared to diplomatic treaties of the ancient Near East, in which a copy was made for each party.[59]

According to the Talmud, the compendium of traditional Rabbinic Jewish law, tradition, and interpretation, one interpretation of the biblical verse "the tablets were written on both their sides",[60] is that the carving went through the full thickness of the tablets, yet was miraculously legible from both sides.[61]

Use in Jewish ritual

The Ten Commandments on a glass plate

The Mishna records that during the period of the Second Temple, the Ten Commandments were recited daily,[62] before the reading of the Shema Yisrael (as preserved, for example, in the Nash Papyrus, a Hebrew manuscript fragment from 150–100 BCE found in Egypt, containing a version of the ten commandments and the beginning of the Shema); but that this practice was abolished in the synagogues so as not to give ammunition to heretics who claimed that they were the only important part of Jewish law,[63][64] or to dispute a claim by early Christians that only the Ten Commandments were handed down at Mount Sinai rather than the whole Torah.[62]

In later centuries rabbis continued to omit the Ten Commandments from daily liturgy in order to prevent a confusion among Jews that they are only bound by the Ten Commandments, and not also by many other biblical and Talmudic laws, such as the requirement to observe holy days other than the sabbath.[62]

Today, the Ten Commandments are heard in the synagogue three times a year: as they come up during the readings of Exodus and Deuteronomy, and during the festival of Shavuot.[62] The Exodus version is read in parashat Yitro around late January–February, and on the festival of Shavuot, and the Deuteronomy version in parashat Va'etchanan in August–September. In some traditions, worshipers rise for the reading of the Ten Commandments to highlight their special significance[62] though many rabbis, including Maimonides, have opposed this custom since one may come to think that the Ten Commandments are more important than the rest of the Mitzvot.[65]

In printed Chumashim, as well as in those in manuscript form, the Ten Commandments carry two sets of cantillation marks. The ta'am 'elyon (upper accentuation), which makes each Commandment into a separate verse, is used for public Torah reading, while the ta'am tachton (lower accentuation), which divides the text into verses of more even length, is used for private reading or study. The verse numbering in Jewish Bibles follows the ta'am tachton. In Jewish Bibles the references to the Ten Commandments are therefore Exodus 20:2–14 and Deuteronomy 5:6–18.

Samaritan

The Samaritan Pentateuch varies in the Ten Commandments passages, both in that the Samaritan Deuteronomical version of the passage is much closer to that in Exodus, and in that Samaritans count as nine commandments what others count as ten. The Samaritan tenth commandment is on the sanctity of Mount Gerizim.

The text of the Samaritan tenth commandment follows:[66]

And it shall come to pass when the Lord thy God will bring thee into the land of the Canaanites whither thou goest to take possession of it, thou shalt erect unto thee large stones, and thou shalt cover them with lime, and thou shalt write upon the stones all the words of this Law, and it shall come to pass when ye cross the Jordan, ye shall erect these stones which I command thee upon Mount Gerizim, and thou shalt build there an altar unto the Lord thy God, an altar of stones, and thou shalt not lift upon them iron, of perfect stones shalt thou build thine altar, and thou shalt bring upon it burnt offerings to the Lord thy God, and thou shalt sacrifice peace offerings, and thou shalt eat there and rejoice before the Lord thy God. That mountain is on the other side of the Jordan at the end of the road towards the going down of the sun in the land of the Canaanites who dwell in the Arabah facing Gilgal close by Elon Moreh facing Shechem.

Christianity

Most traditions of Christianity hold that the Ten Commandments have divine authority and continue to be valid, though they have different interpretations and uses of them.[67] The Apostolic Constitutions, which implore believers to "always remember the ten commands of God," reveal the importance of the Decalogue in the early Church.[68] Through most of Christian history the decalogue was considered a summary of God's law and standard of behaviour, central to Christian life, piety, and worship.[69]

References in the New Testament

During his Sermon on the Mount, Jesus explicitly referenced the prohibitions against murder and adultery. In Matthew 19:16-19 Jesus repeated five of the Ten Commandments, followed by that commandment called "the second" (Matthew 22:34-40) after the first and great commandment.

And, behold, one came and said unto him, Good Master, what good thing shall I do, that I may have eternal life? And he said unto him, Why callest thou me good? there is none good but one, that is, God: but if thou wilt enter into life, keep the commandments.

He saith unto him, Which? Jesus said, Thou shalt do no murder, Thou shalt not commit adultery, Thou shalt not steal, Thou shalt not bear false witness, Honour thy father and thy mother: and, Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself.— Matthew 19:16-19

In his Epistle to the Romans, Paul the Apostle also mentioned five of the Ten Commandments and associated them with the neighbourly love commandment.

Romans 13:8 Owe no man any thing, but to love one another: for he that loveth another hath fulfilled the law.

9 For this, Thou shalt not commit adultery, Thou shalt not kill, Thou shalt not steal, Thou shalt not bear false witness, Thou shalt not covet; and if there be any other commandment, it is briefly comprehended in this saying, namely, Thou shalt love thy neighbour as thyself.

10 Love worketh no ill to his neighbour: therefore love is the fulfilling of the law.— Romans 13:8-10 KJV

Roman Catholicism

In Roman Catholicism, Jesus freed Christians from the rest of Jewish religious law, but not from their obligation to keep the Ten Commandments.[70] It has been said that they are to the moral order what the creation story is to the natural order.[70]

According to the Catechism of the Catholic Church—the official exposition of the Catholic Church's Christian beliefs—the Commandments are considered essential for spiritual good health and growth,[71] and serve as the basis for social justice.[72] Church teaching of the Commandments is largely based on the Old and New Testaments and the writings of the early Church Fathers.[73] In the New Testament, Jesus acknowledged their validity and instructed his disciples to go further, demanding a righteousness exceeding that of the scribes and Pharisees.[74] Summarized by Jesus into two "great commandments" that teach the love of God and love of neighbour,[75] they instruct individuals on their relationships with both.

Orthodox

The Eastern Orthodox Church holds its moral truths to be chiefly contained in the Ten Commandments.[76] A confession begins with the Confessor reciting the Ten Commandments and asking the penitent which of them he has broken.[77]

Protestantism

After rejecting the Roman Catholic moral theology, giving more importance to biblical law and the gospel, early Protestant theologians continued to take the Ten Commandments as the starting point of Christian moral life.[78] Different versions of Christianity have varied in how they have translated the bare principles into the specifics that make up a full Christian ethic.[78]

A Christian school in India displays the Ten Commandments

Lutheranism

The Lutheran division of the commandments follows the one established by St. Augustine, following the then current synagogue scribal division. The first three commandments govern the relationship between God and humans, the fourth through eighth govern public relationships between people, and the last two govern private thoughts. See Luther's Small Catechism[79] and Large Catechism.[29]

Reformed

The Articles of the Church of England, Revised and altered by the Assembly of Divines, at Westminster, in the year 1643 state that "no Christian man whatsoever is free from the obedience of the commandments which are called moral. By the moral law, we understand all the Ten Commandments taken in their full extent."[80] The Westminster Confession, held by Presbyterian Churches, holds that the moral law contained in the Ten Commandments "does forever bind all, as well justified persons as others, to the obedience thereof".[81]

Methodist

The moral law contained in the Ten Commandments, according to the founder of the Methodist movement John Wesley, was instituted from the beginning of the world and is written on the hearts of all people.[82]

As with the Reformed view,[83] Wesley held that the moral law, which is contained in the Ten Commandments, stands today:[84]

Every part of this law must remain in force upon all mankind in all ages, as not depending either on time or place, nor on any other circumstances liable to change; but on the nature of God and the nature of man, and their unchangeable relation to each other" (Wesley's Sermons, Vol. I, Sermon 25).[84]

In keeping with Wesleyan covenant theology, "while the ceremonial law was abolished in Christ and the whole Mosaic dispensation itself was concluded upon the appearance of Christ, the moral law remains a vital component of the covenant of grace, having Christ as its perfecting end."[82] As such, in Methodism, an "important aspect of the pursuit of sanctification is the careful following" of the Ten Commandments.[83]

The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints

According to The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints (LDS) doctrine, Jesus completed rather than rejected the Mosaic Law.[85] The Ten Commandments are considered eternal gospel principles necessary for exaltation.[86] They appear in the Book of Mosiah 12:34–36,[87] 13:15–16,[88] 13:21–24[89] and Doctrine and Covenants.[86] According to the Book of Mosiah, a prophet named Abinadi taught the Ten Commandments in the court of King Noah and was martyred for his righteousness.[90]Abinadi knew the Ten Commandments from the brass plates.[91]

In an October 2010 address, LDS president and prophet Thomas S. Monson taught "The Ten Commandments are just that—commandments. They are not suggestions."[92]

The Strangite denomination has different views of the Decalogue.[citation needed]

Main points of interpretative difference

Sabbath day

All Abrahamic religions observe a weekly day of rest, often called the Sabbath, although the actual day of the week ranges from Friday in Islam, Saturday in Judaism (both reckoned from dusk to dusk), and Sunday, from midnight to midnight, in Christianity. Sabbath in Christianity is a day of rest from work, often dedicated to religious observance, derived from the Biblical Sabbath.[93]Non-Sabbatarianism is the principle of Christian liberty from being bound to physical sabbath observance. Most dictionaries provide both first-day and seventh-day definitions for "sabbath" and "Sabbatarian", among other related uses.

Observing the Sabbath on Sunday, the day of resurrection, gradually became the dominant Christian practice from the Jewish-Roman wars onward.[citation needed] The Church's general repudiation of Jewish practices during this period is apparent in the Council of Laodicea (4th century AD) where Canons 37–38 state: "It is not lawful to receive portions sent from the feasts of Jews or heretics, nor to feast together with them" and "It is not lawful to receive unleavened bread from the Jews, nor to be partakers of their impiety".[94] Canon 29 of the Laodicean council specifically refers to the sabbath: "Christians must not judaize by resting on the [Jewish] Sabbath, but must work on that day, rather honouring the Lord's Day; and, if they can, resting then as Christians. But if any shall be found to be judaizers, let them be anathema from Christ."[94]

Killing or murder

The Sixth Commandment, as translated by the Book of Common Prayer (1549).

The image is from the altar screen of the Temple Church near the Law Courts in London.

Multiple translations exist of the fifth/sixth commandment; the Hebrew words לא תרצח (lo tirtzach) are variously translated as "thou shalt not kill" or "thou shalt not murder".[95]

The imperative is against unlawful killing resulting in bloodguilt.[96] The Hebrew Bible contains numerous prohibitions against unlawful killing, but does not prohibit killing in the context of warfare (1Kings 2:5–6), capital punishment (Leviticus 20:9–16) and self-defence (Exodus 22:2–3), which are considered justified. The New Testament is in agreement that murder is a grave moral evil,[97] and references the Old Testament view of bloodguilt.[98]

Theft

Some academic theologians, including German Old Testament scholar Albrecht Alt: Das Verbot des Diebstahls im Dekalog (1953), suggest that the commandment translated as "thou shalt not steal" was originally intended against stealing people—against abductions and slavery, in agreement with the Talmudic interpretation of the statement as "thou shalt not kidnap" (Sanhedrin 86a).

Idolatry

Idolatry is forbidden in all Abrahamic religions. In Judaism there is a prohibition against worshipping an idol or a representation of God, but there is no restriction on art or simple depictions. Islam has a stronger prohibition, banning representations of God, and in some cases of Muhammad, humans and, in some interpretations, any living creature.

In Gospel of Barnabas, Jesus stated that idolatry is the greatest sin as it divests a man fully of faith, and hence of God.[99] In his time, Idolatry is not only worshipping statues of wood or stone; but also statues of flesh. All which a man loves, for which he leaves everything else but that, is his god, thus the glutton and drunkard has for his idol his own flesh, the fornicator has for his idol the harlot and the greedy has for his idol silver and gold, and so the same for every other sinner.[100]

In Christianity's earliest centuries, some Christians had informally adorned their homes and places of worship with images of Christ and the saints, which others thought inappropriate. No church council had ruled on whether such practices constituted idolatry. The controversy reached crisis level in the 8th century, during the period of iconoclasm: the smashing of icons.[101]

In 726 Emperor Leo III ordered all images removed from all churches; in 730 a council forbade veneration of images, citing the Second Commandment; in 787 the Seventh Ecumenical Council reversed the preceding rulings, condemning iconoclasm and sanctioning the veneration of images; in 815 Leo V called yet another council, which reinstated iconoclasm; in 843 Empress Theodora again reinstated veneration of icons.[101] This mostly settled the matter until the Protestant Reformation, when John Calvin declared that the ruling of the Seventh Ecumenical Council "emanated from Satan".[101] Protestant iconoclasts at this time destroyed statues, pictures, stained glass, and artistic masterpieces.[101]

The Eastern Orthodox Church celebrates Theodora's restoration of the icons every year on the First Sunday of Great Lent.[101] Eastern Orthodox tradition teaches that while images of God, the Father, remain prohibited, depictions of Jesus as the incarnation of God as a visible human are permissible. To emphasize the theological importance of the incarnation, the Orthodox Church encourages the use of icons in church and private devotions, but prefers a two-dimensional depiction[102] as a reminder of this theological aspect. Icons depict the spiritual dimension of their subject rather than attempting a naturalistic portrayal.[101] In modern use (usually as a result of Roman Catholic influence), more naturalistic images and images of the Father, however, also appear occasionally in Orthodox churches, but statues, i.e. three-dimensional depictions, continue to be banned.[102]

The Roman Catholic Church holds that one may build and use "likenesses", as long as the object is not worshipped. Many Roman Catholic Churches and services feature images; some feature statues. For Roman Catholics, this practice is understood as fulfilling the Second Commandment, as they understand that these images are not being worshipped.[citation needed]

Some Protestants will picture Jesus in his human form, while refusing to make any image of God or Jesus in Heaven.[citation needed]

Strict Amish people forbid any sort of image, such as photographs.[citation needed]

Adultery

Originally this commandment forbade male Israelites from having sexual intercourse with the wife of another Israelite; the prohibition did not extend to their own slaves. Sexual intercourse between an Israelite man, married or not, and a woman who was neither married nor betrothed was not considered adultery.[103] This concept of adultery stems from the economic aspect of Israelite marriage whereby the husband has an exclusive right to his wife, whereas the wife, as the husband's possession, did not have an exclusive right to her husband.[104]

Louis Ginzberg argued that the tenth commandment (Covet not thy neighbor's wife) is directed against a sin which may lead to a trespassing of all Ten Commandments.[105]

Critical historical analysis

Early theories

Critical scholarship is divided over its interpretation of the ten commandment texts.

Julius Wellhausen's influential hypothesis regarding the formation of the Pentateuch suggests that Exodus 20-23 and 34 "might be regarded as the document which formed the starting point of the religious history of Israel."[106] Deuteronomy 5 then reflects King Josiah's attempt to link the document produced by his court to the older Mosaic tradition.

In a 2002 analysis of the history of this position, Bernard M. Levinson argued that this reconstruction assumes a Christian perspective, and dates back to Johann Wolfgang von Goethe's polemic against Judaism, which asserted that religions evolve from the more ritualistic to the more ethical. Goethe thus argued that the Ten Commandments revealed to Moses at Mt. Sinai would have emphasized rituals, and that the "ethical" Decalogue Christians recite in their own churches was composed at a later date, when Israelite prophets had begun to prophesy the coming of the messiah, Jesus Christ. Levinson points out that there is no evidence, internal to the Hebrew Bible or in external sources, to support this conjecture. He concludes that its vogue among later critical historians represents the persistence of the idea that the supersession of Judaism by Christianity is part of a longer history of progress from the ritualistic to the ethical.[107]

By the 1930s, historians who accepted the basic premises of multiple authorship had come to reject the idea of an orderly evolution of Israelite religion. Critics instead began to suppose that law and ritual could be of equal importance, while taking different form, at different times. This means that there is no longer any a priori reason to believe that Exodus 20:2–17 and Exodus 34:10–28 were composed during different stages of Israelite history. For example, critical historian John Bright also dates the Jahwist texts to the tenth century BCE, but believes that they express a theology that "had already been normalized in the period of the Judges" (i.e., of the tribal alliance).[108] He concurs about the importance of the decalogue as "a central feature in the covenant that brought together Israel into being as a people"[109] but views the parallels between Exodus 20 and Deuteronomy 5, along with other evidence, as reason to believe that it is relatively close to its original form and Mosaic in origin.[110]

Hittite treaties

According to John Bright, however, there is an important distinction between the Decalogue and the "book of the covenant" (Exodus 21-23 and 34:10–24). The Decalogue, he argues, was modelled on the suzerainty treaties of the Hittites (and other Mesopotamian Empires), that is, represents the relationship between God and Israel as a relationship between king and vassal, and enacts that bond.[111]

"The prologue of the Hittite treaty reminds his vassals of his benevolent acts.. (compare with Exodus 20:2 "I am the LORD your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery"). The Hittite treaty also stipulated the obligations imposed by the ruler on his vassals, which included a prohibition of relations with peoples outside the empire, or enmity between those within."[112] (Exodus 20:3: "You shall have no other gods before Me"). Viewed as a treaty rather than a law code, its purpose is not so much to regulate human affairs as to define the scope of the king's power.[113]

Julius Morgenstern argued that Exodus 34 is distinct from the Jahwist document, identifying it with king Asa's reforms in 899 BCE.[114] Bright, however, believes that like the Decalogue this text has its origins in the time of the tribal alliance. The book of the covenant, he notes, bears a greater similarity to Mesopotamian law codes (e.g. the Code of Hammurabi which was inscribed on a stone stele). He argues that the function of this "book" is to move from the realm of treaty to the realm of law: "The Book of the Covenant (Ex., chs. 21 to 23; cf. ch. 34), which is no official state law, but a description of normative Israelite judicial procedure in the days of the Judges, is the best example of this process."[115] According to Bright, then, this body of law too predates the monarchy.[116]

Hilton J. Blik writes that the phrasing in the Decalogue's instructions suggests that it was conceived in a mainly polytheistic milieu, evident especially in the formulation of the henotheistic "no-other-gods-before-me" commandment.[117][self-published source]

Dating

If the Ten Commandments are based on Hittite forms, it would date them to somewhere between the 14th-12th century BCE.[118] Archaeologists Israel Finkelstein and Neil Asher Silberman argue that "the astonishing composition came together … in the seventh century BCE".[119] Critical scholar Yehezkel Kaufmann (1960) dates the oral form of the covenant to the time of Josiah.[120] An even later date (after 586 BCE) is suggested by David H. Aaron.[121]

The Ritual Decalogue

Some proponents of the Documentary hypothesis have argued that the biblical text in Exodus 34:28[122] identifies a different list as the ten commandments, that of Exodus 34:11–27.[123] Since this passage does not prohibit murder, adultery, theft, etc., but instead deals with the proper worship of Yahweh, some scholars call it the "Ritual Decalogue", and disambiguate the ten commandments of traditional understanding as the "Ethical Decalogue".[124][125][126][127]

According to these scholars the Bible includes multiple versions of events. On the basis of many points of analysis including linguistic it is shown as a patchwork of sources sometimes with bridging comments by the editor (Redactor) but otherwise left intact from the original, frequently side by side.[128]

Richard Elliott Friedman argues that the Ten Commandments at Exodus 20:1–17 "does not appear to belong to any of the major sources. It is likely to be an independent document, which was inserted here by the Redactor."[129] In his view, the Covenant Code follows that version of the Ten Commandments in the northern Israel E narrative. In the J narrative in Exodus 34 the editor of the combined story known as the Redactor (or RJE), adds in an explanation that these are a replacement for the earlier tablets which were shattered. "In the combined JE text, it would be awkward to picture God just commanding Moses to make some tablets, as if there were no history to this matter, so RJE adds the explanation that these are a replacement for the earlier tablets that were shattered."[130]

He writes that Exodus 34:14–26 is the J text of the Ten Commandments: "The first two commandments and the sabbath commandment have parallels in the other versions of the Ten Commandments. (Exodus 20 and Deuteronomy 5). … The other seven commandments here are completely different."[131] He suggests that differences in the J and E versions of the Ten Commandments story are a result of power struggles in the priesthood. The writer has Moses smash the tablets "because this raised doubts about the Judah's central religious shrine".[132]

According to Kaufmann, the Decalogue and the book of the covenant represent two ways of manifesting God's presence in Israel: the Ten Commandments taking the archaic and material form of stone tablets kept in the ark of the covenant, while the book of the covenant took oral form to be recited to the people.[120]

United States debate over display on public property

Ten Commandments display at the Texas State Capitol in Austin.

European Protestants replaced some visual art in their churches with plaques of the Ten Commandments after the Reformation. In England, such "Decalogue boards" also represented the English monarch's emphasis on rule of royal law within the churches. The United States Constitution forbids establishment of religion by law; however images of Moses holding the tablets of the Decalogue, along other religious figures including Solomon, Confucius, and Mohamed holding the Qur'an, are sculpted on the north and south friezes of the pediment of the Supreme Court building in Washington.[133] Images of the Ten Commandments have long been contested symbols for the relationship of religion to national law.[134]

In the 1950s and 1960s the Fraternal Order of Eagles placed possibly thousands of Ten Commandments displays in courthouses and school rooms, including many stone monuments on courthouse property.[135] Because displaying the commandments can reflect a sectarian position if they are numbered (see above), the Eagles developed an ecumenical version that omitted the numbers, as on the monument at the Texas capitol (shown here). Hundreds of monuments were also placed by director Cecil B. DeMille as a publicity stunt to promote his 1956 film The Ten Commandments.[136] Placing the plaques and monuments to the Ten Commandments in and around government buildings was another expression of mid-twentieth century U.S. civil religion, along with adding the phrase "under God" to the Pledge of Allegiance.[134]

By the beginning of the twenty-first century in the U.S., however, Decalogue monuments and plaques in government spaces had become a legal battleground between religious as well as political liberals and conservatives. Organizations such as the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) and Americans United for Separation of Church and State launched lawsuits challenging the posting of the ten commandments in public buildings. The ACLU has been supported by a number of religious groups (such as the Presbyterian Church (U.S.A.),[137] and the American Jewish Congress[138]), both because they do not want government to be issuing religious doctrine and because they feel strongly that the commandments are inherently religious. Many commentators see this issue as part of a wider culture war between liberal and conservative elements in American society. In response to the perceived attacks on traditional society, other legal organizations, such as the Liberty Counsel, have risen to advocate the conservative interpretation. Many Christian conservatives have taken the banning of officially sanctioned prayer from public schools by the U.S. Supreme Court as a threat to the expression of religion in public life. In response, they have successfully lobbied many state and local governments to display the ten commandments in public buildings.

Those who oppose the posting of the ten commandments on public property argue that it violates the establishment clause of the First Amendment to the Constitution of the United States. In contrast, groups like the Fraternal Order of Eagles who support the public display of the ten commandments claim that the commandments are not necessarily religious but represent the moral and legal foundation of society, and are appropriate to be displayed as a historical source of present-day legal codes. Also, some argue like Judge Roy Moore that prohibiting the public practice of religion is a violation of the first amendment's guarantee of freedom of religion.[134]

The Ten Commandments by Lucas Cranach the Elder in the townhall of Wittenberg, (detail)

U.S. courts have often ruled against displays of the Ten Commandments on government property. They conclude that the ten commandments are derived from Judeo-Christian religions, to the exclusion of others: the statement "Thou shalt have no other gods before me" excludes non-monotheistic religions like Hinduism, for example. Whether the Constitution prohibits the posting of the commandments or not, there are additional political and civil rights issues regarding the posting of what is construed as religious doctrine. Excluding religions that have not accepted the ten commandments creates the appearance of impropriety. The courts have been more accepting, however, of displays that place the Ten Commandments in a broader historical context of the development of law.

One result of these legal cases has been that proponents of displaying the Ten Commandments have sometimes surrounded them with other historical texts to portray them as historical, rather than religious. Another result has been that other religious organizations have tried to put monuments to their laws on public lands. For example, an organization called Summum has won court cases against municipalities in Utah for refusing to allow the group to erect a monument of Summum aphorisms next to the ten commandments. The cases were won on the grounds that Summum's right to freedom of speech was denied and the governments had engaged in discrimination. Instead of allowing Summum to erect its monument, the local governments chose to remove their ten commandments.

Cultural references

Two famous films of this name were directed by Cecil B. DeMille: a silent movie released in 1923 starring Theodore Roberts as Moses and a colour VistaVision version of 1956, starring Charlton Heston as Moses.

Both Dekalog, a 1989 Polish film series directed by Krzysztof Kieślowski, and The Ten, a 2007 American film, use the ten commandments as a structure for 10 smaller stories.[139]

The receipt of the Ten Commandments by Moses was satirized in Mel Brooks's movie History of the World Part I (1981), which shows Moses (played by Brooks, in a similar costume to Charlton Heston's Moses in the 1956 film), receiving three tablets containing fifteen commandments, but before he can present them to his people, he stumbles and drops one of the tablets, shattering it. He then presents the remaining tablets, proclaiming Ten Commandments.[140]

In The Prince of Egypt, a 1998 animated film that depicted the early life of Moses (voiced by Val Kilmer), the ending depicts him with the Ten Commandments at Mount Sinai, accompanied by a reprise of Deliver Us.

The story of Moses and the Ten Commandments is discussed in the Danish stageplay Biblen (2008).

See also

Alternatives to the Ten Commandments – Secular and humanist alternatives to the biblical lists

Code of Hammurabi (1772 BCE)

Code of Ur-Nammu (2050 BCE)- Five Precepts

- Five Precepts (Taoism)

Maat, 42 confessions, ' The negative confession ' (1500 BCE) of Papyrus of Ani, also known as The declaration of innocence before the Gods of the tribunal from The book of going forth by day, also Book of the dead

The Ten Commandments (2007 film)- K10C: Kids' Ten Commandments

- Ten Commandments of Computer Ethics

- Ten Conditions of Bai'at

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Ten Commandments. |

References

^ "UBA: Rosenthaliana 1768" [English: 1768: The Ten Commandments, copied in Amsterdam Jekuthiel Sofer] (in Dutch). Retrieved 26 April 2012.

^ Rooker, Mark (2010). The Ten Commandments: Ethics for the Twenty-First Century. Nashville, Tennessee: B&H Publishing Group. p. 3. ISBN 0-8054-4716-4. Retrieved 2011-10-02.The Ten Commandments are literally the 'Ten Words' (ăśeret hadděbārîm) in Hebrew. The use of the term dābār, 'word,' in this phrase distinguishes these laws from the rest of the commandments (mişwâ), statutes (hōq), and regulations (mišpāţ) in the Old Testament.

^ ab "Exodus 34:28 – multiple versions and languages". Studybible.info. Retrieved 2012-12-09.

^ δεκάλογος. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project

^ "Deuteronomy 10:4 – multiple versions and languages". Studybible.info. Retrieved 2012-12-09.

^ Chan, Yiu Sing Lúcás (2012). The Ten Commandments and the Beatitudes. Lantham, MA: Rowman & Littlefield. pp. 38, 241.

^ ab Block, Daniel I. (2012). "The Decalogue in the Hebrew Scriptures". In Greenman, Jeffrey P.; Larsen, Timothy. The Decalogue Through the Centuries: From the Hebrew Scriptures to Benedict XVI. Westminster John Knox Press. pp. 1–27. ISBN 0-664-23490-9.

^ ab I am the LORD your God, who brought you out of the land of Egypt, out of the house of slavery.

^ ab You shall have no other gods before me.

^ ab You shall not make for yourself a carved image, or any likeness of anything that is in heaven above, or that is in the earth beneath, or that is in the water under the earth. You shall not bow down to them or serve them, for I the LORD your God am a jealous God, visiting the iniquity of the fathers on the children to the third and the fourth generation of those who hate me, but showing steadfast love to thousands of those who love me and keep my commandments.

^ ab You shall not take the name of the LORD your God in vain, for the LORD will not hold him guiltless who takes his name in vain.

^ Remember the Sabbath day, to keep it holy. Six days you shall labor, and do all your work, but the seventh day is a Sabbath to the LORD your God. On it you shall not do any work, you, or your son, or your daughter, your male slave, or your female slave, or your livestock, or the sojourner who is within your gates. For in six days the LORD made heaven and earth, the sea, and all that is in them, and rested on the seventh day. Therefore the LORD blessed the Sabbath day and made it holy.

^ Observe the Sabbath day, to keep it holy, as the LORD your God commanded you. Six days you shall labor and do all your work, but the seventh day is a Sabbath to the LORD your God. On it you shall not do any work, you or your son or your daughter or your male slave or your female slave, or your ox or your donkey or any of your livestock, or the sojourner who is within your gates, that your male slave and your female slave may rest as well as you. You shall remember that you were a slave in the land of Egypt, and the LORD your God brought you out from there with a mighty hand and an outstretched arm. Therefore the LORD your God commanded you to keep the Sabbath day.

^ Honor your father and your mother, that your days may be long in the land that the LORD your God is giving you.

^ Honor your father and your mother, as the LORD your God commanded you, that your days may be long, and that it may go well with you in the land that the LORD your God is giving you.

^ ab You shall not murder.

^ You shall not commit adultery.

^ And you shall not commit adultery.

^ You shall not steal.

^ And you shall not steal.

^ You shall not bear false witness against your neighbor.

^ And you shall not bear false witness against your neighbor.

^ You shall not covet your neighbor's house

^ And you shall not desire your neighbor's house, his field,

^ You shall not covet your neighbor's wife …

^ And you shall not covet your neighbor's wife.

^ … or his male slave, or his female slave, or his ox, or his donkey, or anything that is your neighbor's.

^ … or his male slave, or his female slave, his ox, or his donkey, or anything that is your neighbor's.

^ ab Luther's Large Catechism (1529)

^ Fincham, Kenneth; Lake, Peter (editors) (2006). Religious Politics in Post-reformation England. Woodbridge, Suffolk: The Boydell Press. p. 42. ISBN 1-84383-253-4. CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link)

^ When LORD is printed in small caps, it typically represents the so-called Tetragrammaton, a Greek term representing the four Hebrews YHWH which indicates the divine name. This is typically indicated in the preface of most modern translations. For an example, see Crossway Bibles (28 December 2011), "Preface", Holy Bible: English Standard Version, Wheaton: Crossway, p. IX, ISBN 978-1-4335-3087-6, retrieved 19 November 2012

^ Deuteronomy 4:13, 5:22

^ Somer, Benjamin D. Revelation and Authority: Sinai in Jewish Scripture and Tradition (The Anchor Yale Bible Reference Library). pg = 40.

^ Exodus 20:21

^ Exodus 21–23

^ Exodus 24:4

^ Exodus 24:7

^ Exodus 24:1,9

^ Exodus 24:1–11

^ Exodus 24:16–18

^ Deuteronomy 9:10

^ Ex. 32:1–5

^ Ex. 32:6–8

^ Ex.32:19

^ Ex. 34:1

^ Deuteronomy 10:4

^ Exodus.20:1;Exodus.32:15–19

^ Deuteronomy.4:10–13;Deut.5:22;Deut.9:17;Deut.10:1–5

^ abc Herbert Huffmon, "The Fundamental Code Illustrated: The Third Commandment," in The Ten Commandments: The Reciprocity of Faithfulness, ed. William P. Brown., pp. 205–212. Westminster John Knox Press (2004). ISBN 0-664-22323-0

^ Miller, Patrick D. (2009). The Ten Commandments. Presbyterian Publishing Corp. pp. 4–12. ISBN 0-664-23055-5.

^ Milgrom, Joseph (2005). "The Nature of Revelation and Mosaic Origins". In Blumenthal, Jacob; Liss, Janet. Etz Hayim Study Guide. Jewish Publication Society. pp. 70–74. ISBN 0-8276-0822-5.

^ ab William Barclay, The Ten Commandments. Westminster John Knox Press (2001), originally The Plain Man's Guide to Ethics (1973). ISBN 0-664-22346-X

^ abc Gail R. O'Day and David L. Petersen, Theological Bible Commentary, p. 34, Westminster John Knox Press (2009) ISBN 0-664-22711-2

^ Norman Solomon, Judaism, p. 17. Sterling Publishing Company (2009) ISBN 1-4027-6884-2

^ Wayne D. Dosick, Living Judaism: The Complete Guide to Jewish Belief, Tradition, and Practice, pp. 31–33. HarperCollins (1995). ISBN 0-06-062179-6 "There are 603 more Torah commandments. But in giving these ten — with their wise insight into the human condition — God established a standard of right and wrong, a powerful code of behavior, that is universal and timeless."

^ Ginzberg, Louis, The Legends of the Jews, Vol. III: The Unity of Ten Commandments, (Translated by Henrietta Szold), Johns Hopkins University Press: 1998, ISBN 0-8018-5890-9

^ Talmud Makkos 1:10

^ Rabbi Ishmael. Horowitz-Rabin, ed. Mekhilta. pp. 233, Tractate de–ba–Hodesh, 5.

^ Margaliot, Dr. Meshulam (July 2004). "What was Written on the Two Tablets?". Bar-Ilan University. Retrieved 2006-09-20.

^ Exodus 32:15

^ Babylonian Talmud, tractate Shabbat 104a.

^ abcde Simon Glustrom, The Myth and Reality of Judaism, pp 113–114. Behrman House (1989). ISBN 0-87441-479-2

^ Yerushalmi Berakhot, Chapter 1, fol. 3c. See also Rabbi David Golinkin, Whatever Happened to the Ten Commandments?

^ Talmud. tractate Berachot 12a.

^ Covenant & Conversation Yitro 5772 Archived 24 May 2015 at the Wayback Machine. Chief Rabbi. Retrieved 24 May 2015

^ Gaster, Moses (1923). "The Samaritan Tenth Commandment". The Samaritans, Their History, Doctrines and Literature. The Schweich Lectures.

^ Braaten, Carl E.; Seitz, Christopher (2005). "Preface". I Am the Lord Your God. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans. p. x. – via Questia (subscription required)

^ Roberts, Alexander (1 May 2007). The Ante-Nicene Fathers. VII. Cosimo, Inc. p. 413. ISBN 9781602064829.

^ Turner, Philip (2005). "The Ten Commandments in the Church in a Postmodern World". In Braaten, Carl E.; Seitz, Christopher. I Am the Lord Your God. Grand Rapids, MI: William B. Eerdmans. p. 3. – via Questia (subscription required)

^ ab Jan Kreeft, Catholic Christianity: A Complete Catechism of Catholic Beliefs Based on the Catechism of the Catholic Church, ch. 5. Ignatius Press (2001). ISBN 0-89870-798-6

^ Kreeft, Peter (2001). Catholic Christianity. Ignatius Press. ISBN 0-89870-798-6. pp. 201–203 (Google preview p.201)

^ Carmody, Timothy R. (2004). Reading the Bible. Paulist Press. ISBN 978-0-8091-4189-0. p. 82

^ Paragraph number 2052–2074 (1994). "Catechism of the Catholic Church". Libreria Editrice Vaticana. Retrieved 8 June 2009.

^ Kreeft, Peter (2001). Catholic Christianity. Ignatius Press. ISBN 0-89870-798-6. p. 202 (Google preview p.202)

^ Schreck, Alan (1999). The Essential Catholic Catechism. Servant Publications. ISBN 1-56955-128-6. p. 303

^ Sebastian Dabovich, Preaching in the Russian Church, p. 65. Cubery (1899).

^ Alexander Hugh Hore, Eighteen Centuries of the Orthodox Church, p. 36. J. Parker and Co. (1899).

^ ab Timothy Sedgwick, The Christian Moral Life: Practices of Piety, pp. 9–20. Church Publishing (2008). ISBN 1-59627-100-0

^ Luther's Small Catechism (1529)

^ Neal, Daniel (1843). The History of the Puritans, Or Protestant Non-conformists. Harper. p. 3.|access-date=requires|url=(help)

^ "Westminster Confession of Faith: Chapter XIX - Of the Law of God". Retrieved 23 June 2017.

^ ab Rodes, Stanley J. (25 September 2014). From Faith to Faith: John Wesley’s Covenant Theology and the Way of Salvation. James Clarke & Co. p. 69. ISBN 9780227902202.

^ ab Campbell, Ted A. (1 October 2011). Methodist Doctrine: The Essentials, 2nd Edition. Abingdon Press. pp. 40, 68–69. ISBN 9781426753473.

^ ab The Sabbath Recorder, Volume 75. George B. Utter. 1913. p. 422.The moral law contained in the Ten Commandments and enforced by the prophets, he (Christ) did not take away. It was not the design of his coming to revoke any part of this. This is a law which never can be broken. It stands fast as the faithful witness in heaven.

^ Olmstead, Thomas F. "The Savior's Use of the Old Testament". Ensign. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. p. 46. Retrieved November 28, 2013.

^ ab "Ten Commandments". Gospel Library. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints. Retrieved November 28, 2013.

^ "Mosiah 12:34–36". Lds.org. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

^ "Mosiah 13:15–16". Lds.org. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

^ "Mosiah 13:20–24". Lds.org. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

^ Cramer, Lew W. (1992). "Abinadi". In Ludlow, Daniel H. Encyclopedia of Mormonism. New York: Macmillan. pp. 5–7. Retrieved November 28, 2013.

^ Mosiah 13:11–26 :The Ten Commandments: "Some may wonder how Abinadi could have read the Ten Commandments that God gave to Moses. It should be remembered that the brass plates Nephi obtained contained the five books of Moses (Nephi 5:10–11). This record, which would have contained the Ten Commandments, had been passed down by Nephite prophets and record keepers. The previous scriptures were known to King Noah and his priests because they quoted from Isaiah and referred to the law of Moses (see Mosiah 12:20–24, 28)."

^ Thomas S. Monson. "Stand in Holy Places - Thomas S. Monson". Lds.org. Retrieved 2016-01-20.

^ (Hebrew: שַׁבָּת, shabbâth, Hebrew word #7676 in Strong's Concordance, meaning intensive "repose").

^ ab Synod of Laodicea (4th Century) – New Advent

^ Exodus 20:13 Multiple versions and languages.

^ Bloodguilt, Jewish Virtual Library, Genesis 4:10, Genesis 9:6, Genesis 42:22, Exodus 22:2–2, Leviticus 17:4, Leviticus 20, Numbers 20, Deuteronomy 19, Deuteronomy 32:43, Joshua 2:19, Judges 9:24, 1 Samuel 25, 2 Samuel 1, 2 Samuel 21, 1 Kings 2, 1 Kings 21:19, 2 Kings 24:4, Psalm 9:12, Psalm 51:14, Psalm 106:38, Proverbs 6:17, Isaiah 1:15, Isaiah 26:21, Jeremiah 22:17, Lamentations 4:13, Ezekiel 9:9, Ezekiel 36:18, Hosea 4:2, Joel 3:19, Habakkuk 2:8, Matthew 23:30–35, Matthew 27:4, Luke 11:50–51, Romans 3:15, Revelation 6:10, Revelation 18:24

^ Matthew 5:21, Matthew 15:19, Matthew 19:19, Matthew 22:7, Mark 10:19, Luke 18:20, Romans 13:9, 1 Timothy 1:9, James 2:11, Revelation 21:8

^ Matthew 23:30–35, Matthew 27:4, Luke 11:50–51, Romans 3:15, Revelation 6:10, Revelation 18:24

^ Chapter 32: Statues of Flesh Barnabas.net

^ Gospel of Barnabas chapter XXXIII Latrobe Edu

^ abcdef Archpriest John W. Morris, The Historic Church: An Orthodox View of Christian History, chapter 7. AuthorHouse (2011) ISBN 1-4567-3492-X

^ ab Alexander Hugh Hore, Eighteen Centuries of the Orthodox Church, J. Parker and co. (1899)

"The images or Icons, as they are called, of the Greek Church are not, it must be remarked, sculptured images, but flat pictures or mosaics; not even the Crucifix is sanctioned; and herein consists the difference between the Greek and Roman Churches, in the latter of which both pictures and statues are allowed, and venerated with equal honour." p.353

^ Collins, R. F. (1992). "Ten Commandments." In D. N. Freedman (Ed.), The Anchor Yale Bible Dictionary (Vol. 6, p. 386). New York: Doubleday

^ "''Encyclopedia Judaica'' vol01 pg 424". Jewishvirtuallibrary.org. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

^ Ginzberg, Louis, The Legends of the Jews, Vol. III: The other Commandments Revealed on Sinai, (Translated by Henrietta Szold), Johns Hopkins University Press: 1998, ISBN 0-8018-5890-9

^ Julius Wellhausen 1973 Prolegomena to the History of Israel Glouster, MA: Peter Smith. 392

^ Levinson, Bernard M. (July 2002). "Goethe's Analysis of Exodus 34 and Its Influence on Julius Wellhausen: the Pfropfung of the Documentary Hypothesis". Zeitschrift für die Alttestamentliche Wissenschaft 114 (2): 212–223

^ John Bright 1972 A History of Israel Second Edition. Philadelphia: the Westminster Press. 142–143

4th edition p.146-147 ISBN 0-664-22068-1

^ Bright, John (2000). A History of Israel (4 ed.). Westminster John Knox Press. p. 146. Retrieved 2012-12-09.

^ John Bright, 1972 A History of Israel Second Edition. Philadelphia: the Westminster Press. 142 4th ed. p.146+

^ John Bright, 1972, p., 146–147 4th ed. p.150–151

^ Cornfeld, Gaalyahu Ed Pictorial Biblical Encyclopedia, MacMillan 1964 p. 237

^ John Bright, 1972, p., 165 4th ed. p.169–170

^ Morgenstern, Julius (1927), The Oldest Document of the Hexateuch, IV, HUAC

^ Bright, John, 2000, A History of Israel 4th ed. p.173.

^ John Bright, 1972, p. 166 4th ed. p.170+

^ "The point here being underscored is that the Decalogue represents an earlier stage in the development of this tradition, and the Ten Commandments, when critically viewed, do not only NOT demand a monotheistic adherence, they clearly presuppose and affirm a polytheistic reality! Those who attempt to impose a principle of monotheism on the Ten Commandments are simply anticipating the historical development of the tradition ahead of its time and are thus already assuming what they pretend to discover." (Tyranny, Taboo, and the Ten Commandments: The Decalogue Decoded And Its Impact on Civil Society, Hilton J. Bik, Xlibris Corporation 2008, p.199).

^ Israel Finkelstein, Neil Asher Silberman (2002). The Bible Unearthed. p 63. ISBN 0-7432-2338-1

^ Israel Finkelstein, Neil Asher Silberman (2002). The Bible Unearthed, p. 70.

^ ab Yehezkal Kaufmann 1960 The Religion of Israel: From its beginnings to the Babylonian Exile trans. and Abridged by Moshe Greenberg. New York: Schocken Books, p. 174–175.

^ ""Etched in Stone: The Emergence of the Decalogue"" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 October 2011. (99.8 KB), The Chronicle, Hebrew Union College – Jewish Institute of Religion, Issue 68, 2006, p. 42. "a critical survey of biblical literature demonstrates no cognizance of the ten commandments prior to the post-exilic period (after 586 B.C.E.)"

^ Exodus 34:28

^ Exodus 34:11–27

^ The New Oxford Annotated Bible with the Apocrypha. Augmented Third Edition, New Revised Standard Version, 2007

^ The Hebrew Bible: A Brief Socio-Literary Introduction. Norman Gottwald, 2008

^ Dictionary of the Old Testament: Pentateuch. T. Desmond Alexander and David Weston Baker, 2003

^ Commentary on the Torah. Richard Elliott Friedman, 2003

^ Friedman, Richard Elliott. The Bible with Sources Revealed, 2003 p. 7

^ Friedman, p. 153

^ Friedman, p. 177

^ Friedman, p. 179

^ Friedman, Richard Elliott. "Who Wrote The Bible?" 1987 pp. 73–74

^ Office of the Curator, "Courtroom Friezes: North and South Walls" (PDF). Supreme Court of the United States, 5/8/2003.

^ abc Watts, "Ten Commandments Monuments" (PDF). 2004

^ Emmet V. Mittlebeeler,

(2003) "Ten Commandments." P. 434 in The Encyclopedia of American Religion and Politics. Edited by P. A. Djupe and L. R. Olson. New York: Facts on File.

^ "MPR: The Ten Commandments: Religious or historical symbol?". News.minnesota.publicradio.org. 2001-09-10. Retrieved 2012-12-09.

^ PCUSA Assembly Committee on General Assembly Procedures D.3.a http://apps.pcusa.org/ga216/business/commbooks/comm03.pdf[permanent dead link]

^ American Jewish Congress, "AJCongress Voices Opposition to Courtroom Display of ten Commandments," (May 16, 2003) http://www.ajcongress.org/site/PageServer?pagename=may03_03

^ The Ten (2007) – IMDb

^ "Fifteen Commandments". YouTube.com. 2012-08-10. Retrieved 2018-04-05.

Further reading

This article's further reading may not follow Wikipedia's content policies or guidelines. Please improve this article by removing less relevant or redundant publications with the same point of view; or by incorporating the relevant publications into the body of the article through appropriate citations. (June 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this template message) |

Aaron, David H (2006). Etched in Stone: The Emergence of the Decalogue. Continuum. ISBN 0-567-02791-0.

Abdrushin (2009). The Ten Commandments of God and the Lord's Prayer. Grail Foundation Press. ISBN 1-57461-004-X. https://web.archive.org/web/20100523082204/http://the10com.org/index.html- Peter Barenboim, Biblical Roots of Separation of Powers, Moscow, 2005, ISBN 5-94381-123-0.

Boltwood, Emily (2012). 10 Simple Rules of the House of Gloria. Tate Publishing. ISBN 978-1-62024-840-9.

Freedman, David Noel (2000). The Nine Commandments. Uncovering a Hidden Pattern of Crime and Punishment in the Hebrew Bible. Doubleday. ISBN 0-385-49986-8.

Friedman, Richard Elliott (1987). Who Wrote the Bible?. Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice Hall. ISBN 0-671-63161-6.

Hazony, David (2010). The Ten Commandments: How Our Most Ancient Moral Text Can Renew Modern Life. New York: Scribner. ISBN 1-4165-6235-4.

Kaufmann, Yehezkel (1960). The Religion of Israel, From Its Beginnings To the Babylonian Exile. Translated by Moshe Greenberg. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Kuntz, Paul Grimley (2004). The Ten Commandments in History: Mosaic Paradigms for a Well-Ordered Society. Wm B Eerdmans Publishing, Emory University Studies in Law and Religion. ISBN 0-8028-2660-1.- Markl, Dominik (2012): "The Decalogue in History: A Preliminary Survey of the Fields and Genres of its Reception", in: Zeitschrift für Altorientalische und Biblische Rechtsgeschichte – vol. 18, nº., pp. 279–293. (pdf)

Markl, Dominik (ed.) (2013). The Decalogue and its Cultural Influence. Sheffield: Sheffield Phoenix Press. ISBN 978-1-909697-06-5. CS1 maint: Extra text: authors list (link)

Mendenhall, George E (1973). The Tenth Generation: The Origins of the Biblical Tradition. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0-8018-1267-4.

Mendenhall, George E (2001). Ancient Israel's Faith and History: An Introduction To the Bible In Context. Louisville: Westminster John Knox Press. ISBN 0-664-22313-3.

Watts, James W. (2004). "Ten Commandments Monuments and the Rivalry of Iconic Texts" (PDF). Journal of Religion and Society. 6. Retrieved 2014-08-27.

External links

- Ten Commandments: Ex. 20 version (text, mp3), Deut. 5 version (text, mp3) in The Hebrew Bible in English by Jewish Publication Society, 1917 ed.

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Comments

Post a Comment