Manchester Royal Infirmary

| Manchester Royal Infirmary | |

|---|---|

Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust | |

MRI's main building in 1957 | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Chorlton on Medlock, Manchester, North West England, United Kingdom, England |

| Organisation | |

| Care system | NHS |

| Hospital type | Teaching |

| Affiliated university | Manchester Medical School |

| Services | |

| Emergency department | Yes Major Trauma Centre |

| Beds | 750 or more[1][2] |

| History | |

| Founded | 1752 |

| Links | |

| Website | http://www.cmft.nhs.uk/ |

| Lists | Hospitals in England |

Manchester Royal Infirmary is a hospital in Manchester, England, founded by Charles White in 1752. It is now part of Manchester University NHS Foundation Trust, sharing buildings and facilities with several other hospitals.

The Infirmary itself specialises in cardiology, in renal medicine and surgery and in kidney and pancreas transplants. Its A&E department deals with around 145,000 patients every year.[3] The transplant team carried out 317 transplants in 2015, the most of any centre in the UK.[4]

Contents

1 Beginning

2 New Infirmary

2.1 Manchester Lunatic Asylum

2.2 Public baths

2.3 Development

3 Royal Infirmary

3.1 Architecture

3.2 Students

4 Oxford Road

4.1 Second World War

5 See also

6 References

7 Further reading

8 External links

Beginning

The first premises was a house in Garden Street, off Withy Grove, Manchester, which were opened on Monday 27 July 1752, financed by subscriptions. Government of the institution was in the hands of the trustees. Any subscriber who paid 2 guineas a year was a trustee. Those who donated 20 guineas became a trustee for life. The trustees appointed physicians and surgeons by voting. In 1835 900 trustees assembled to vote in the town hall. Joseph Jordan was elected, having secured 466 votes. He had spent £690, mostly on hiring vehicles to bring his supporters in to vote. By 1855 the subscription was 3 guineas, or a donation of 30 guineas.

There were initially three physicians and three surgeons, Charles White being one. White co-founded the Infirmary with local industrialist Joseph Bancroft in 1752, and was an honorary surgeon there until 1790.[5] One patient, John Boardman, suffering from Scrofula was treated. The first inpatient was admitted on 3 August, Benjamin Dooley, aged 12, suffering from "sordid ulcers in the leg" In 1753 it was decided to purchase surgical instruments and to establish a dispensary.[6]

New Infirmary

A model of the premises in the present-day Piccadilly Gardens

Manchester Royal Infirmary (a 19th century engraving)

It was decided to build a new hospital in 1753 on land leased from Sir Oswald Mosley, lord of the manor, who granted a 999-year lease at an annual rent of £6. The site had previously been called the Daub Holes: these pits, 615 feet long, had filled with water and they were replaced by a fine ornamental pond.[7]

The new premises had space for eighty beds and were on Lever's Row in the area now known as Piccadilly Gardens (the gardens were only created after the demolition of the former MRI buildings in 1914). The new building was opened on 9 June 1755. It had three stories and cellars. The first student, John Daniel, was taken on as an apprentice to the apothecary. By 1756 it was already necessary to add a new wing to the north to house a laundry and wash house. In 1764 there were 85 inpatients. Patients sometimes shared a bed.

[8]

Manchester Lunatic Asylum

The building of the Manchester Lunatic Asylum on the same site as the main hospital was completed in 1765. In 1846 it was removed to Cheadle, Cheshire.

Public baths

In 1779 public baths were built on the site. Cold baths were 6d (2½p), a Buxton bath 1/- (5p), a warm bath 1/-, and a vapour bath or use of the seating room 5/- (25p). Prices were doubled on Sunday. It was also possible to pay an annual fee. The baths were very popular and profitable. People with venereal disease were not allowed in the Buxton Baths, which were heated to 92 °F (33 °C). and held 3,400 gallons. The Matlock Bath held 6,200 and was heated to 92 degrees. F. William and Ann Howarth were appointed to run the baths in 1799, and they were subsequently known as Howarth's Baths. A steam engine was installed for pumping and heating water for the baths and the hospital. During 1808 4,654 baths were taken by the public – not counting those taken by anyone belonging to the infirmary. In 1813 the waterworks company agreed to supply water to the baths and hospital free of charge. In 1836 the bathman was paid £160, and an additional allowance for washing towels. The average annual profit was £95. In 1847 it was decided to close the baths.

Development

A scheme for inoculating poor people for smallpox was started in 1784. They were attended, when necessary, in their own homes, as were people with contagious diseases. Jenner's scheme of vaccination was enthusiastically adopted in 1800, and 1,000 people were vaccinated in six months. In 1790 two physicians were appointed to deal with home visits. A new building for out patients and the dispensary was completed and the hospital was officially titled "The Infirmary, Dispensary, Lunatic Hospital and Asylum in Manchester". There were now six physicians and six surgeons. A library was established in the Infirmary in 1791. Dr John Ferriar, one of the physicians, helped to set up a Board of Health which rented 4 houses in Portland Street belonging to the Lunatic Asylum for use as a fever hospital. It was called the House of Recovery and patients from the rest of the infirmary were moved there if they had infectious diseases. In 1793 a new north wing was built, with room for 50 more beds.

In 1824 the Board noted that it had become impossible to admit all the patients in need of care. Erysipelas had become a problem on surgical wards as a result of overcrowding. £5,600 was raised to fund further extensions, which were opened in 1828. The extension included nurses kitchens, 8 water closets, a wash house and laundry, and an accident room and surgery. There were now "upwards of 180 beds", but the surgical wards were still overcrowded and patients were forced to share beds. In the two years 1838–40 there were 143 operations and 36 of the patients died. A chaplain was appointed for the first time in 1838.

In 1841 there were 67 medical and 125 surgical beds, after the removal of some of the double beds. Mortality of inpatients was 12%.

Royal Infirmary

The infirmary was renamed the Manchester Royal Infirmary Dispensary, Lunatic Hospital and Asylum in 1830.[9]

During 1831 and 1832 110 operations were performed by the house surgeons. 62 were limb amputations. During 1843 one of the rooms in the asylum was taken over by the infirmary, which was still crowded.

In 1835 the total expenditure was £11,700. £1,064 was spent on salaries, £355 on wine, £290 on leeches.

With the removal of the asylum in 1846 the trustees embarked on an expansion programme. Jenny Lind gave two concerts for the benefit of the funds in December 1848 and raised £2,512. The newly built wings were heated by hot water pipes and lit by gas. There were now 220 beds. The number of home visits by the physicians' clerks for patients with infectious disease had risen to more than 5,000 a year. Three of the clerks contracted fever and one died. There were a total of 310 beds in 1855 when the fever hospital was closed. Mortality rose to its highest level, 14.7%, in 1860/61, although about a fifth of deaths happened within 24 hours of admission. This level was not unusual in hospitals at this period.

In 1859 there were 7 resident doctors, 27 nurses and 51 servants. Arrangements with Devonshire Royal Hospital and Southport Promenade Hospital for convalescent care were established. In 1867 Cheadle Hall was first rented and then purchased and equipped for the care of 30 convalescent patients. It was renamed the Barnes Convalescent Home in recognition of donations of £26,000 by Robert Barnes.

Monsall Hospital was established in North Manchester in 1871 as a fever hospital. Robert Barnes donated £9,000 and the hospital was named the Barnes House of Recovery. Manchester City Council contributed £500. The total cost was £13,000. There was accommodation for 128 fever patients and room to separate patients suffering from different infections. In 1875 there were 843 admissions, mostly with smallpox.

In 1870 Mr Lund, one of the surgeons, started to use Lister's antiseptic methods, and by 1875 this had become routine practice.

Telephones were first installed in 1880, free of charge by courtesy of the Lancashire and Cheshire Telephone Company, a clinical laboratory erected in the grounds in 1898, and x-rays began in 1904. The x-ray machine was housed in the chapel as no other space could be found.

Architecture

In 1832 two new porticos, each with four Ionic columns, had been completed. By the late 19th century statues had been installed on the esplanade on the northern side while the streets to the south beyond Parker Street were narrow.[10]

The old building was completely demolished by April 1910.

Students

Organised admission of medical pupils began in 1793. The fee for the first six-month session was 5 guineas, and for two subsequent sessions 3 guineas with extra fees payable to surgeons for attendance at operations. in 1817 fees for apprentices were 200 guineas, paid after completion of a three-month probation period. Apprenticeship lasted at least 5 years and the fee covered board and lodging. They were increased to 260 guineas in 1824 [11] Students in the 19th century were awarded external degrees by the University of London.[12] It is unclear when lectures began but there are records dating from 1834. By 1854 there were regular weekly lectures. The formal involvement of Owens College in medical training dates from 1893, when it was agreed that beds would be provided in the infirmary for professors if they were not already on the staff.

For many years students at the university ran an eleaborate rag on Shrove Tuesday each year, and by 1938 they had collected a total of £100,000, which was commemorated by a plaque on the wall of the hospital.

Systematic training of nurses only began in 1864. There were 11 probationary nurses in 1868, admitted for three months training.

A catalogue of the library was compiled by Frank Renaud and published in 1859.[13] A collection of books from the library was donated to the Medical Library of the university in 1917.

Plaque on the wall of Manchester Royal Infirmary

Oxford Road

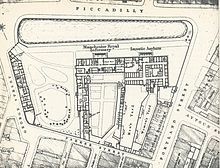

Plan of Manchester Royal Infirmary

Discussions about moving the infirmary to its present site in Oxford Road started in 1875, and a plan was finally agreed in 1904. The Picadilly site was sold to the City Council for £400,000 and plans for new buildings designed by Edwin Hall and John Brooke were accepted after a competition. The new building cost £500,000 and was opened on 1 December 1908. There were 48 wards – surgical and medical coming off two parallel corridors on three floors. Medical wards had 50 beds and surgical wards had 60 with an operating theatre for each surgical unit.

A radiology department was not envisaged in the plans, but Dr Barclay, appointed in 1909, established a department in the basement. In 1913 more than 5,000 patients were examined radiologically. Radiotherapy for cancer patients started in 1914 and the Manchester and District Radium Institute was established in a building next to the hospital in 1921.

208 beds were made available for sick and wounded soldiers during the First World War. A total of 10,077 soldiers were treated as inpatients during the war, chiefly for surgery. A centre for the treatment of venereal disease was established in 1918, and dealt with 837 people in that year.

A school of massage was established in 1919. By 1920 it had 47 students.

In 1930 a new nurses' home, Sparshott House, was built. It had 263 single bedrooms. Nurses in 1924 had been working 63 hours a week on day duty or 73 hours on night duty. There were then 220 nurses and 113 maidservants.

A self-contained unit for private patients with 100 beds was built in 1937 with its own kitchens and operating theatres and was financially self-supporting.

It was not until 1933 that the official title of the hospital was changed to the Manchester Royal Infirmary.[14]

Second World War

On 28 August 1939 400 patients were evacuated and 440 beds prepared for expected casualties. By November 1939, in the absence of the expected casualties all the beds were brought back into use. A large emergency blood transfusion centre was established and continued after the war.

A high explosive bomb penetrated the new nurses' home in 11 October 1940. 112 nurses were in the basement shelters, but nobody was hurt. However none of the rooms could be used and the nurses had to sleep elsewhere, including in the university. Within a month 130 bedrooms were back in use. The biggest raids on Manchester were on 22 and 23 December 1940. On the first night very few actually struck the hospital buildings but most of the windows were blown out. 10,000 panes of glass had to be replaced. On the first night 186 casualties were admitted and 400 more treated in the casualty and first aid posts. On the second night a time bomb fell on the X-ray and teaching block which exploded on the following day, 24 December, putting the heating of the entire hospital out of action. There were no casualties to patients or staff, but there was extensive demolition subsequently.

In 1942 agreement was reached with the City Council that the whole area of what was called the Island Site, bounded by Hathersage Road, Upper Brook Street, Grafton Street and Oxford Road should be kept for hospital and associated purposes.

In 1944 the hospital was a receiving station for the casualties of the D-Day landings. During the war the government met the expenses of the hospitals and salaries for nurses and other staff were raised substantially. In 1946 the Trustees were faced with a wage bill £92,000 higher than in 1939 and the total running expenses of the hospital were double compared to 1939. Income had risen by £60,000, largely due to the Hospital Saturday Fund. It was clear that under the plans for the NHS the hospitals on the site would be regarded as one big teaching hospital, and would have a substantial degree of autonomy. But in 1946/47 the hospital made a loss of £152,000.

In 1950 a new neurology and neurosurgery unit was built, with its own operating block.

View of the front of the Infirmary from the other side of Oxford Road

| Year | Admitted | Cured | Died | Outpatients | Costs |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1752 | 75 | 42 | 3 | 249 | £405 |

| 1762 | 402 | 841 | £1,169 | ||

| 1777 | 473 | 21 | 1,256 | ||

| 1802 | 705 | 50 | 3,470 | £4,000 | |

| 1848 | 2,056 | 191 | 18,200 | £8,400 | |

| 1852 | £8,400 | ||||

| 1863 | 1,730 | ||||

| 1874 | 2,735 | ||||

| 1885 | 4,500 | 21,700 | |||

| 1902 | 4,500 | 35,800 | |||

| 1913 | 9,049 | 55,900 | |||

| 1919 | 11,550 | 7% | 44,071 | ||

| 1933 | 11,928 | 5.8% | 51,000 | ||

| 1946–47 | 10,845 | 5.5% | 54,184 | £400,000 |

See also

- Healthcare in Greater Manchester

- List of hospitals in England

References

^ "Manchester Royal Infirmary, Manchester". Retrieved 20 June 2007.

^ "MRI web pages". Manchester Royal Infirmary. Retrieved 8 October 2009.

^ Manchester Royal Infirmary

^ "Annual Report Summary 2015/16". Central Manchester University Hospital.|access-date=requires|url=(help)

^ Butler, Stella (2004). "White, Charles (1728–1813)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 6 February 2009.

^ Brockbank, William (1952). Portrait of a Hospital. London: William Heinemann. pp. 10–42.|access-date=requires|url=(help)

^ Atkins, Philip (1976). Guide Across Manchester. Manchester: Civic Trust for the North West. ISBN 0-901347-29-9.

^ Brockbank, William (1952). Portrait of a Hospital. London: William Heinemann. p. 25.|access-date=requires|url=(help)

^ Whitehead, Walter (2 August 1902). "President's Address Delivered, At The Seventieth Annual Meeting of the British Medical Association, Manchester's Early Influence on the Advancement of Medicine And Medical Education". The British Medical Journal. BMJ Publishing Group. 2 (2170): 301–313. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.2170.301. JSTOR 20273139. (subscription required)

^ Brockbank, E. M. (1929) "The Hospitals of Manchester and Salford". In: Book of Manchester and Salford. Manchester: Falkner & Co.; pp. 116–19, 2 views

^ Brockbank, William (1952). Portrait of a Hospital. London: William Heinemann. pp. 28–112.|access-date=requires|url=(help)

^ "Student lists". Archived from the original on 14 September 2010. Retrieved 7 October 2010.

^ Axon, William (1877) Handbook of the Public Libraries of Manchester and Salford. Manchester: Abel Heywood and Son; pp. 127–28

^ Brockbank, William (1952). Portrait of a Hospital. London: William Heinemann. pp. 119–177.|access-date=requires|url=(help)

Further reading

Pickstone, John (19–26 December 1987). "Manchester's History And Manchester's Medicine". British Medical Journal (Clinical Research Edition). BMJ Publishing Group. 295 (6613): 1604–1608. doi:10.1136/bmj.295.6613.1604. JSTOR 29529232.- Valier, Helen K. (2007) "The Manchester Royal Infirmary, 1945-97: a microcosm of the National Health Service", in: Bulletin of the John Rylands University Library of Manchester; vol. 87, no. 1 (2005)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Manchester Royal Infirmary. |

- Manchester Royal Infirmary

Coordinates: 53°27′44″N 2°13′35″W / 53.46222°N 2.22639°W / 53.46222; -2.22639

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Clash Royale CLAN TAG#URR8PPP

Comments

Post a Comment